Ephemera & Elegy

The artistic friendship of Jimmy Wright and Arch Connelly III

A new show titled Trajectory at the University Museum at Southern Illinois University/Carbondale, pairs the work of New York Artists Jimmy Wright and Arch Connelly III - both with ties to SIU.

I was lucky enough to meet Jimmy during his visit to SIU, where he held a fascinating roundtable discussion for students, and a lively public guest lecture at the museum on his life in New York, his friendship with Arch Connelly, and his take on the history and current state of the art scene in New York City.

Tricksters and Tradition

Both gay artist that worked from the 1970s in New York, Wright and Connolly were friends since their days as graduate students at Southern Illinois University/Carbondale.

In Trajectory: Arch Connelly III and Jimmy Wright, the work shares the same room and shows that a difference in approach and direction doesn’t preclude - and perhaps strengthens - a deep artistic connection between two very different artists.

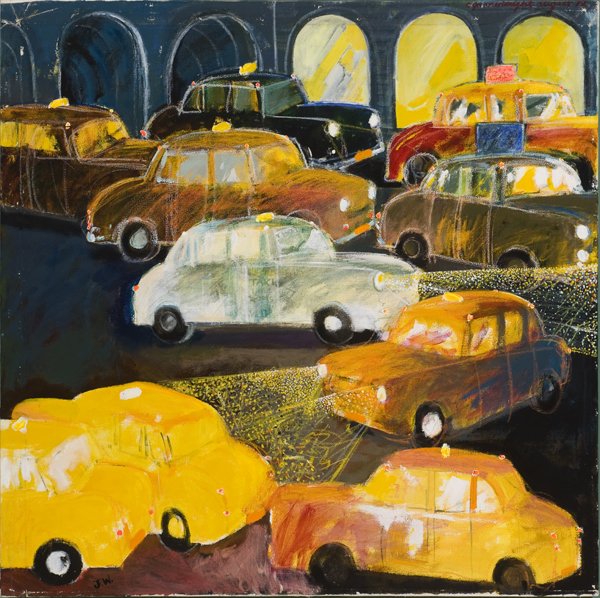

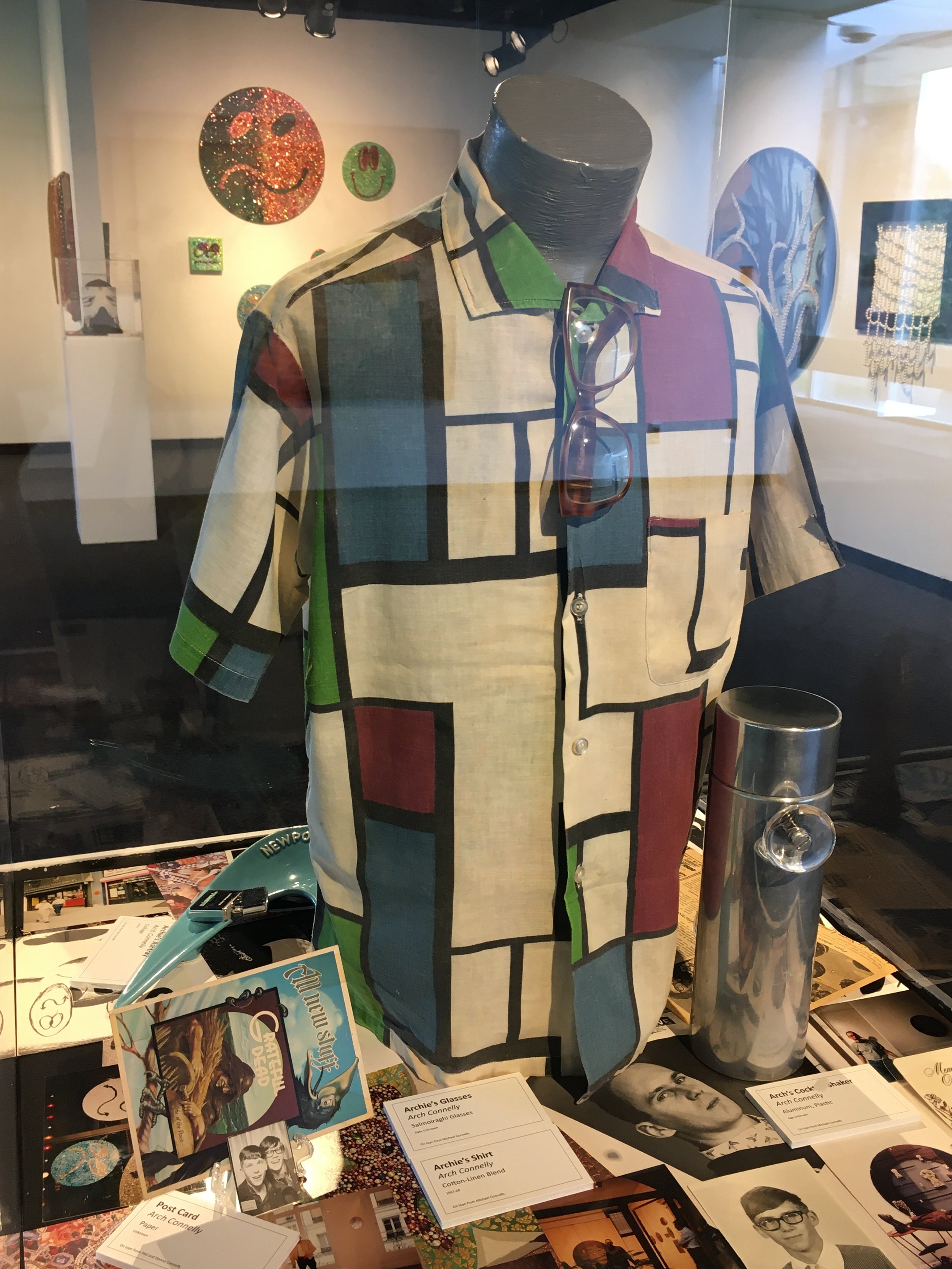

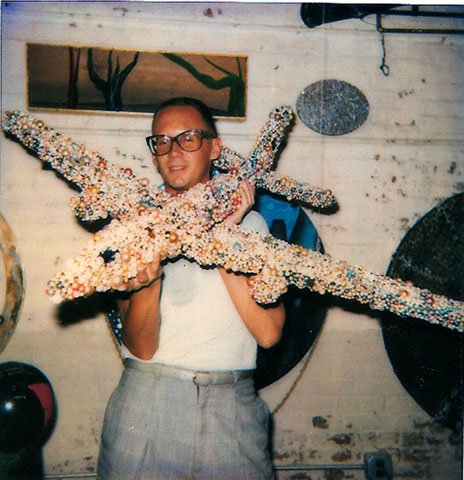

While Connelly’s work - at least in this show, consists of found objects and unconventional assemblages, such as faux pearls affixed to a rondo format, Wright’s work is more traditional in a formal sense.

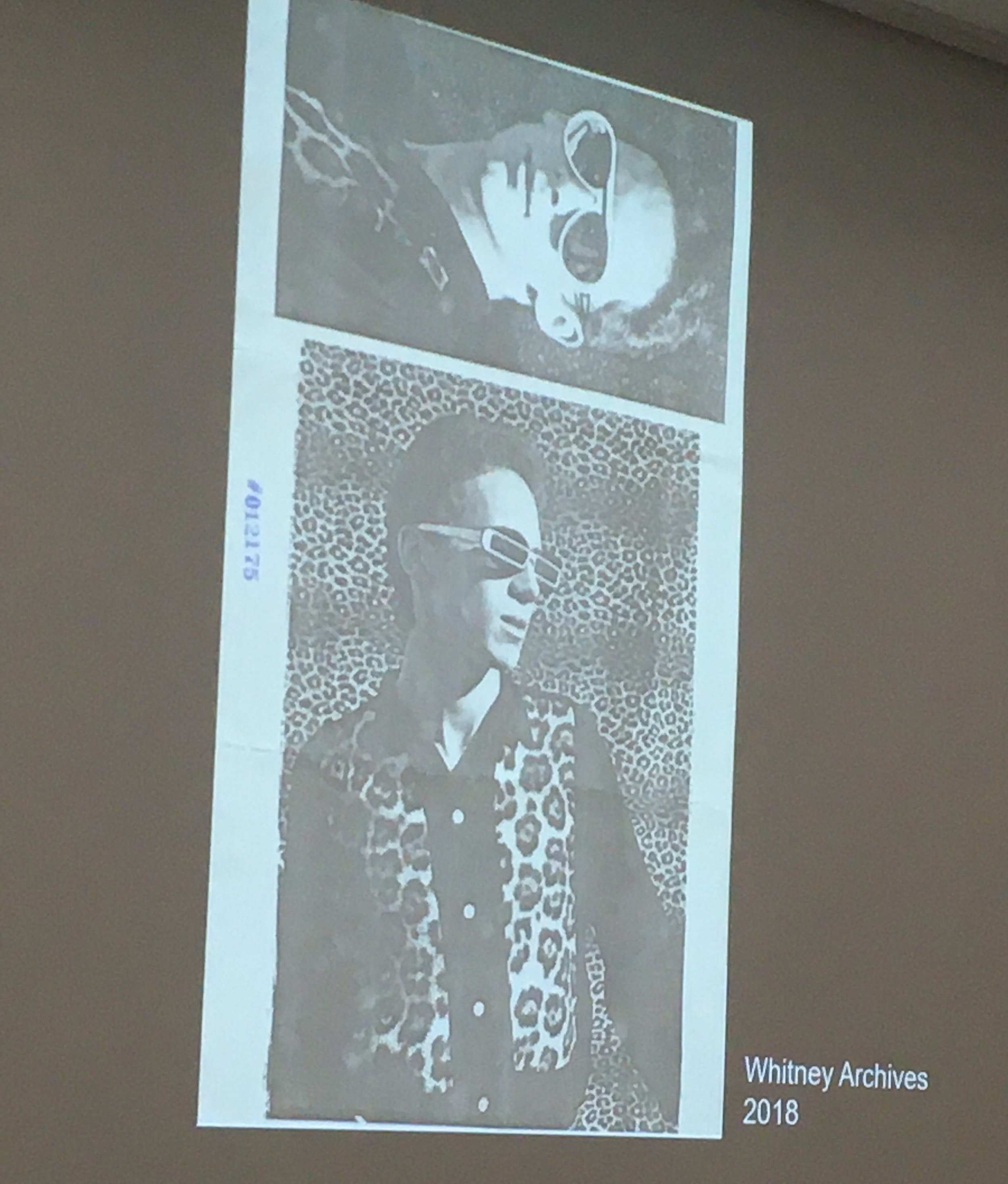

I remember seeing Connelly’s work on a trip to New York in the late 1990s and being struck by the awkward beauty of the beaded sculptures. Connelly was a boyish, flamboyant in a New Wave sort of way, into vintage and leopard skin, old stuff and new music, Bowie, The Who, Iggy Pop. Just like I was. He was a trickster and rabble rouser fascinated with ephemera and oddities of the early 20th century thrift store culture.

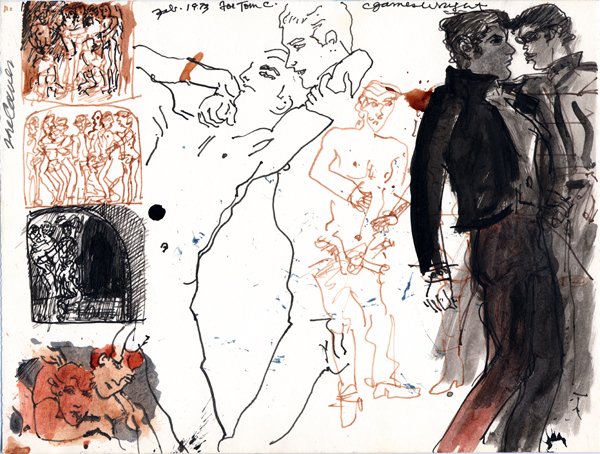

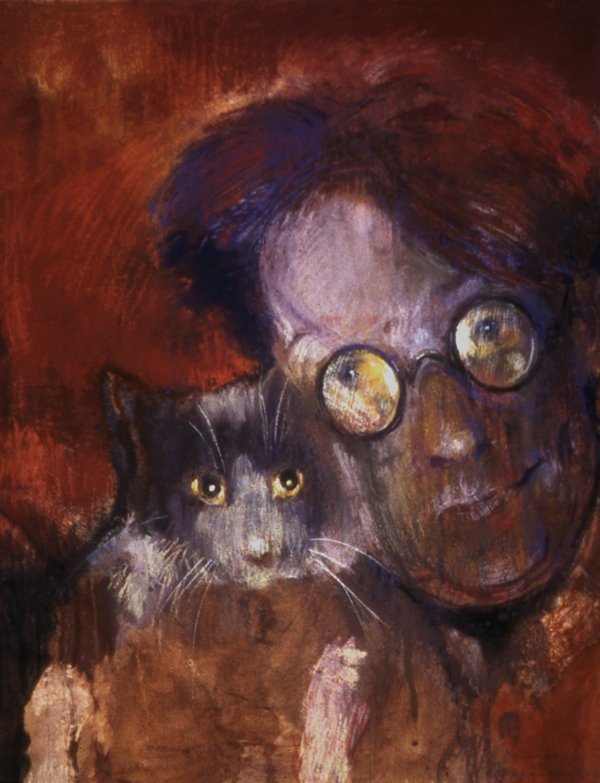

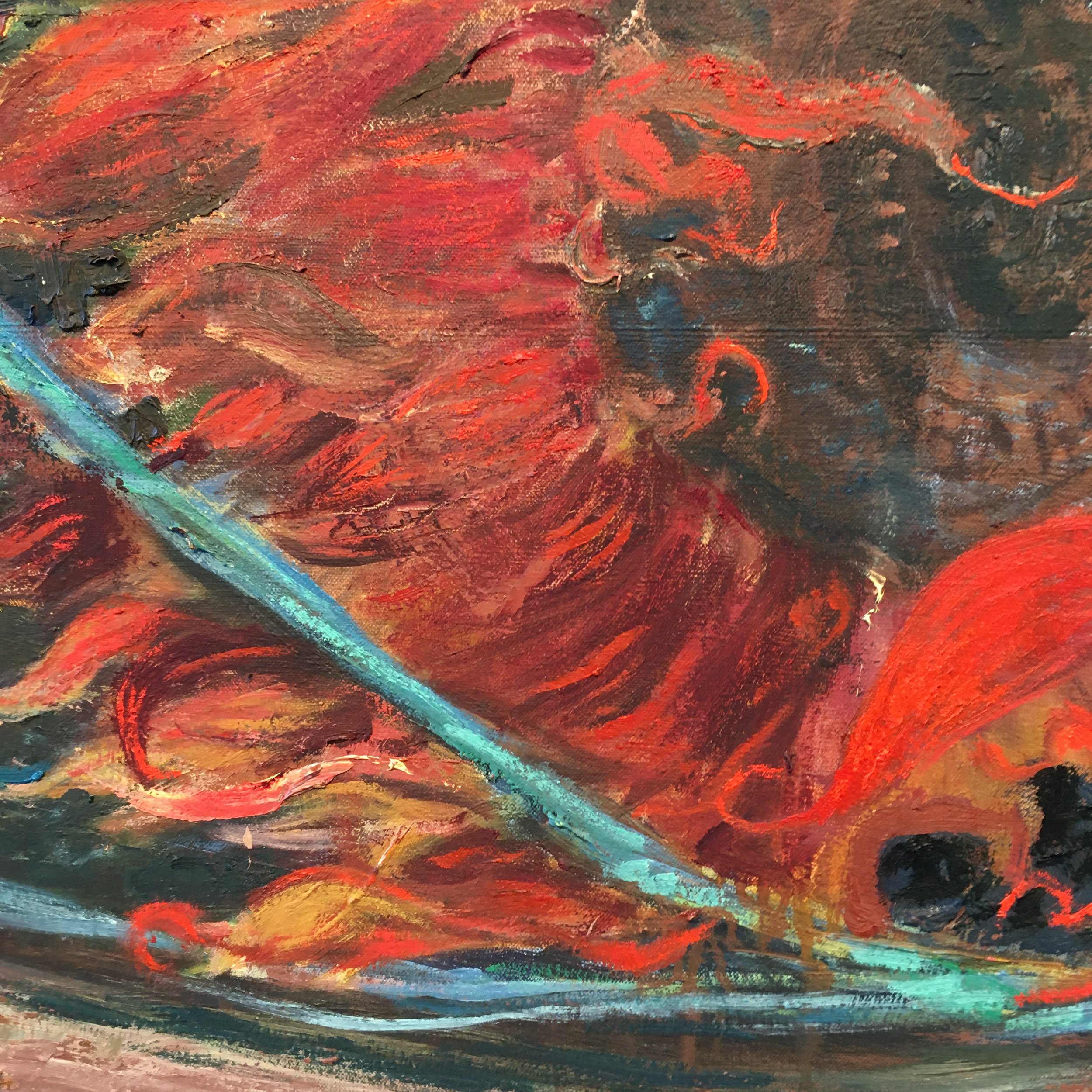

Wright’s work, on the other hand, is based in a solid control of drawing from observation, an astute use of color, and exudes a painterly beauty. But as I heard Wright speak, I realized the trickster in Wright’s personality is present, too - if just a bit more beneath the surface. These two artist friends are in a sense extremes of each other, with Wright’s work coming out of the history of painting, and Connelly’s work more inspired by the found objects of pop culture. But what they have in common is their immersion in the gay scenes of New York and San Francisco - both responding to it in their own deep way.

In his discussions, Wright emphasized the books that influenced him most as a young artist - the complete works of Carl Jung and Paul Klee - and his work reflects a formalism filtered through the concepts of dream, mythology, abstraction, intimacy, and emotion that both of these thinkers explore.

Connelly, on the other hand, prioritized playfulness, an unorthodox use of materials, the ephemeral objects of his zeitgeist layered over preconceived historical notions of landscape, self portrait, and still life. He had an ironic, puckish streak that to me feels radically free from cynicism - a joy for the chance to play with it all, and he seemed to see the world as a playground from which he freely sourced his materials and ideas.

Travel and Tragedy

These two friends and compatriots both came from small towns of the midwest and south, then went off to see the world, bouncing from coast to coast and landing in New York in the 70s, a time of innocence amid experience. The Vietnam War raged and the New York gay scene was in its open burgeoning heyday, when the Battery was burned out and life eventually transitioned into the tragedy of the 80s AIDS epidemic. Wright lost his partner Ken in the late 1980s, and then Connelly succumbed in 1993.

Wright’s Flowers for Ken series of 6-foot by 6-foot oil paintings overflowing with dead and dying flowers seem to revel in the acceptance of their fate, even as color and light pass across every surface.

Wright tended Ken for three years and painted these still lives, as he told us in his roundtable discussion, out of a desperation to find a way to work amid the chaos of Ken’s illness. He said that he could return to the still life set ups again and again, even as they wilted, to find their forms ever shifting, yet somehow a stable, comforting cycle of life amidst his own intimate tragedy.

Archiving an Artistic Friendship

For Wright and Connelly, the New York City of the 70s and 80s was a playground and a struggle, but Wright said, “the reward was I got to be myself,“ socially, sexually, and artistically.

The farm boys made the city their own, building relationships with galleries step-by-step, from the Midtown Payson and DC Moore galleries of the 80s, to having their work acquired by the Whitney and Museum of Modern Art. Wright archived these decades of grit and glitter by stowing ephemera, drawings, postcards, and music posters. He said that after he lost everything but a few singed drawings in the house fire that destroyed his MFA graduate work in 1971, he later “needed to refill the archive“ and so he collected memories from his friends and their lives, from art, to objects, postcards, music posters, party invitations, and more.

What began as a personal collection of historical objects and documents is a treasure trove for the likes of the Whitney Museum to acquire for their collections.

Wright is a model for artists who want to see their lives as art. To him, every memory is important. His formal education led him to develop artistic language of elegy that is both traditional and edgy. his generous storytelling and advice for artists was to embrace both education and experience, for instance, incorporating a practice of painting self-portraits - in order to watch your progress in painting the figure, as well as to chronicle an artist’s development and life.

His huge flower paintings gather the energy of his own trajectory, recalling the formal tradition of the memento mori of the Dutch still life masters, as well as Van Gogh’s self-reflexive sunflower studies, along with the unexpected color and loose brushwork that captures the emotions of both an explosion of grief and celebration of life.

Trajectory: Arch Connelly III and Jimmy Wright is on view at University Museum through December 15, 2023.